Thresholds (2025)

The Shelf as a Site of Meaning

Shelves – these quiet lines, splicing the surface of our walls. Though seemingly simple objects, they are also thresholds, gathering with the weather of life. Dust, our discarded selves lightly pool on their surfaces amongst which we nestle objects that we wish to remember.

Shelf carved into a Neolithic site in Çatalhöyük in Anatolia c.7400-6200 BCE

Niches, carved and worked and smoothed by hand over time can be found in Neolithic dwellings such as Çatalhöyük in Anatolia, occupied between c.7400–6200 BCE. These small, deliberate and personal nooks signify that the people who lived there felt importance for things – that they felt they had ownership, that they believed they had certain rights over things and, more importantly, that the value they held for those things meant that they personally had value too. Whether it held a carved figures, a savoured morsel of food or simply a useful antler, the things held there, had presence and weight. Each thing belonged.

Tokonoma shelf (with plate)

Across rooms and worlds, the same gesture is repeated. From the flagstone shelves in the blustery Neolithic island settlement on Skara Brae in Orkney 3100–2500 BCE where humans hunkered from the elements – to the calm, decorated and sepia saturated tokonoma (display alcoves) found in houses of the Japanese Muromachi Period (1333-1573 CE). Shelves shape our habitats, creating a topography of inquiry.

When books arrived, shelves grew into repositories of thought. They held time spent with fictional characters, with compendiums of our history, with treatises of shareable concepts and philosophies. They became the places where we held the weight of our world and our world came to represent ourselves.

In 2010, one of my first jobs was to clear out the homes of people who had donated their book collections to Amnesty International UK. This was heavy work, hodding 30-by-40 cardboard bricks up and down stairwells and across the city in white Luton vans, wheel arches grinding from the weight.

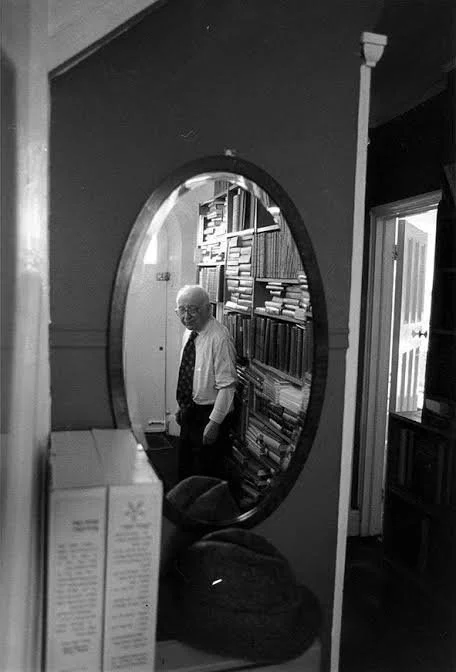

Chimen Abramsky at his home near Hampstead Heath

On one occasion, I was sent to the house of a recently deceased socialist scholar and bibliophile named Chimen Abramsky. I can still recall the thick smell of the dusty room in which he died, clutching a Hebrew bible. Yet despite the situation it wasn’t depressing or unsettling, instead it was deeply fascinating. For every single room in this semi-detached house in Hampstead Heath, was stacked floor to ceiling with creaking books and bowing journals, full with the weight of a man’s lifelong love. Over and around each door, every square inch of every single room had had custom shelving made for what was said to be over twenty thousand volumes. He loved books and in return they had provided him a career. Now they were to be disseminated across London to shelve the homes of new families.

Today the whole sweep of human text sits at our fingertips, yet much of it feels weightless. In many houses today the shelf has grown thin. Flat packed lengths of hollow particle board are filled with the forgettable.

As too with our digital shelves, playlists, tabs, watchlists, folders all promise a return which very rarely comes. These arrangements have little gravity. They do not shape time. They do not slow a hand or a gaze. They will not endure like those sandstone Neolithic niches in Anatolia.

Out in the woods, the land reminds us what a shelf can be. Bracket fungi step from the bark in quiet tiers. Swallows under eaves build ledges of mud and straw. Limestone breaks to form natural cornices where saxifrage roots in the cool seam. Even the sea writes shelves into the coast, terraces of shingle and weed that mark old high water. Nature knows how to lift and hold, how to make a platform for presence.

A well kept shelf borrows that patience. It asks for selection. A river stone found on a day of clear light. A feather from the path’s edge. A book that has taught you a way of seeing. A photograph that softens the air as you pass. These are small offerings to our memory and attention.

They slow the room.

They teach the eye.

To dwell.